“It is not given to human beings – happily for them, otherwise life would be intolerable – to foresee or predict to any large extent the unfolding of events. In one phase men seem to have been right, in another they seem to have been wrong. Then again, a few years later, when the perspective of time has lengthened, all stands in a different setting. There is a new proportion. There is another scale of values. History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes.” –Winston Churchill

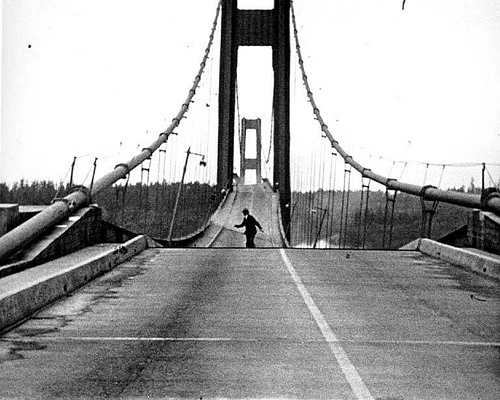

As a much younger man, Churchill witnessed some of the most epic military failures of all time. In the decades before WWI there were no serious wars. This left plenty of room for academics to theorize about how new technology might be used in war; in fact, WWI was possibly the most thoroughly planned war in history.

Yet from the first encounter, the theories unraveled in the face of situations that could never have been predicted. The most respected generals in the world were made to look like amateurs. Their faith in abstract planning blinded them to the reality of the situation. It took years of conflict before they began to really adapt to the reality of their situation.

These generals didn’t realize that they were engaging in the world’s first truly modern battles. These battles required the ability to improvise more than they required detailed plans.

The same transition is currently happening in business. A plethora of business books came out this summer building on the concept of The Lean Startup methodology introduced by Eric Ries. That is, it is cheaper in most cases to run an experiment than to create a plan. Even massive companies are starting to turn their focus towards quickly implementing a strategy on a small scale to test a concept before rolling out a massive change.

Poke and prod rather than plan and plan.

This has implications not just in business on a grand scale, but on an individual level as well. Twenty-year career plans aren’t effective anymore. The amount of variables in our lives has multiplied, and with that, every day seems to contain growing uncertainty. There seem to be two schools of thought on how to deal with this increasing inconstancy:

- The Technophiles: These are the guys who say you should embrace everything that’s new. Technology will annihilate uncertainty. The aim is to integrate ourselves with machines as much as possible.

- The Paleophiles: These are the guys who say you should reject anything new, recover our ancient human history, and live according to that (effectively ignoring new uncertainties). Technology is making us less human. The aim is to detach ourselves from technology.

My goal here is to take a more sober look at ways to deal with (and even benefit from) the ever-increasing uncertainty of daily life. This isn’t a “middle” path of half-measures between the two views, but a totally new way to approach things.

Two Types of Uncertainty

The first thing to understand about our unpredictable world is that there are two types of uncertainty:

- Soft Uncertainty. This is the uncertainty you feel inside yourself. It encompasses the moral, spiritual, or philosophic uncertainties in your life, and the doubt that surrounds your choices in what to do and which way to go. It’s the uncertainty you feel before asking for a raise. It’s the uncertainty you feel before attempting a project. It’s the uncertainty of the existential crisis. It’s the uncertainty in the minds of generals at the start of WWI.

- Hard Uncertainty. This is uncertainty that exists outside of you. It’s the uncertainty that exists after you ask for a raise and after you begin your new project. It resides in the probabilities and randomness of the world. This uncertainty is the work of the Fates. This is the type of uncertainty that soccer moms and economic planners fail to solve, every time. It’s the fact that weapons will be used in ways never imagined.

If we look at these as problems, they are impossible to solve.

Soft Uncertainty seems, at first glance, to be a solvable problem. Just adopt the proper mindset – often that of some religion, nation, or political stance – and you’ll be golden. Many of us, however, are unable to adopt some ideology whole-heartedly.

Hard Uncertainty also seems like a lost cause. Each time we are promised some scientific or economic certainty, the forecasts miss and everything changes.

The problem isn’t uncertainty itself. The problem is our rejection of it.

Perhaps we don’t need to solve Soft Uncertainty by finding the answer. Maybe the ability to comfortably hold a paradox in our mind is the better answer.

Perhaps we can’t control Hard Uncertainty. Maybe we ought to position ourselves to actually benefit from things out of our control.

The tools we discuss below develop our strength to handle both types of uncertainty simultaneously.

Instead of becoming arrogantly certain, we will become confident in our uncertainty. Instead of pretending we can predict the future, we will be ready for a future we could never imagine.

“You get pseudo-order when you seek order; you get a measure of order and control when you embrace randomness.” –Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Some Things Are Certain

Let’s not forget that there are areas in life that are certain. John Kay explains the differences in Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Achieved Indirectly:

“If you are clear about your high-level goals and knowledgeable enough about the systems their achievement depends on, then you can solve problems in a direct way. But goals are often vague, interactions unpredictable, complexity extensive, problem descriptions incomplete, the environment uncertain. That is where obliquity comes into play.”

The world isn’t pure chaos. If you want to learn to tie a bow tie, then you can find instructions on exactly how to do that. If you want to get fit, you know you’ll go far by eating less crap and working harder in the gym. It’s when you begin building a business, starting a romantic relationship, or writing a book that things get more complex. (Sure, there are best practices for these complex tasks, but these will only take you so far.)

These uncertain areas are the most interesting and the most valuable; they provide the most challenge, and thus the most growth, satisfaction, and ultimately, joy. It’s where your time is best spent, and where the concept of obliquity mentioned above factors in. Some problems — the complex ones, especially — require indirect solutions and the ebb and flow of a risk and discovery cycle.

The best chance you have at taking advantage of an uncertain world is to be operating with the proper framework. The tools below will take you a long way in developing that framework.

5 Tools for Dealing With Uncertainty

We are going to look at five tools for dealing with uncertainty through the emotional and professional lens, but understand that this is for the sake of space; many of these have the potential to benefit you in all areas of life where uncertainty resides. Which is to say, everywhere.

1. Stoicism: Focus On What You Can Control

When I was a day trader I would often lose thousands of dollars while making what I believed to be the correct trade. The next day I might make thousands of dollars while executing a foolish trade on a whim. If I allowed my emotions to tie themselves to these outcomes I would have gone broke within a month.

In an uncertain world we might have a great outcome follow a terrible choice or a terrible outcome follow a great choice.

The best we can do is stack the probability of winning in our favor and then act consistently towards winning.

This is terribly difficult because it hurts especially bad to lose while doing the “right” thing.

Stoicism is a powerful tool to help us through the emotional turmoil that this can cause.

Even more than any Roman philosopher, Nassim Nicholas Taleb has summed up what it means to be a modern Stoic:

“Stoicism is about the domestication, not necessarily the elimination, of emotions. It is not about turning humans into vegetables. My idea of the modern Stoic sage is someone who transforms fear into prudence, pain into information, mistakes into initiation, and desire into undertaking.”

William Irvine has written the only true guidebook to modern Stoicism that exists (the Stoics didn’t bother with this, which tells you a lot about the differences between their minds and ours). In it, he describes one of the most important topics of Stoicism: control what you can, forget about the rest. He uses a tennis match to illustrate:

“Remember that among the things over which we have complete control are the goals we set for ourselves. I think that when a Stoic concerns himself with things over which he has some but not complete control, such as winning a tennis match, he will be very careful about the goals he sets for himself. In particular, he will be careful to set internal rather than external goals. Thus, his goal in playing tennis will not be to win a match (something external, over which he has only partial control) but to play to the best of his ability in the match (something internal, over which he was complete control). By choosing this goal, he will spare himself frustration or disappointment should he lose the match: Since it was not his goal to win the match, he will not have failed to attain his goal, as long as he played his best. His tranquility will not be disrupted.”

This is easier said than done. It takes constant practice to separate your emotions from external situations.

How do we go about this?

Every time you begin to feel anxious or upset, try practicing the Triad of Control. To do this, you simply distinguish, in any given situation, whether you have total control, no control, or some control. Then, focus on what is in your control with your whole being.

At first glance it seems like this may rob you of power. It’s acknowledging that you can’t, in fact, control everything. After some practice, though, you will notice a growing sense of control in your life. Instead of tiring yourself worrying about what-ifs and shoulding all over yourself, you are concerned with what you are able to do. You connect yourself to reality.

If you practice this consistently for a month or so you will notice that you actually seek out adversity. Consider Seneca’s description of a wise man:

“So far… is he from shrinking from the buffetings of circumstances or of men, that he counts even injury profitable, for through it he finds a means of putting himself to the proof and makes trial of his virtue.”

Working toward that mindset will make you a force in an uncertain world. You don’t hide when things shift, you push harder. You’re not afraid to learn when new skills become necessary. You aren’t afraid to see opportunities where others only see chaos.

For more on Stoicism check out Ryan Holiday’s quick and motivating The Obstacle is the Way, Tim Ferriss’s favorite essay by Seneca, or, if you want something comprehensive, William Irvine’s A Guide to the Good Life.

If you’d rather visit the primary texts (which are extremely readable and approachable; these guys were more concerned with solving problems than sounding smart) then I’d suggest Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic or Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations to start.

2. Make Many Small Bets

“People are bad at looking at seeds and guessing what size tree will grow out of them.” –Paul Graham

In most situations, it’s cheaper to test the validity of something than to spend a lot of time guessing about it.

In my business, StartupBros, we will use a blog post (investment: time) to gauge demand for information on a certain topic. We have an idea of what types of posts will hit, but we can never be certain. If a post elicits an extreme reaction from readers we consider building a paid course or coaching program based on that topic.

We make small bets (blog posts) and then pour more resources into the ones that show promise.

Venture capital funds operate in a similar way. They never know what is going to be the next Google or Facebook and so they are forced to make a ton of small bets, knowing that most of them won’t work out.

Paul Graham, founder of Y-Combinator, discusses the odd place this puts venture capitalists in:

“When you interview a startup and think ‘they seem likely to succeed,’ it’s hard not to fund them. And yet, financially at least, there is only one kind of success: they’re either going to be one of the really big winners or not, and if not it doesn’t matter whether you fund them, because even if they succeed the effect on your returns will be insignificant. In the same day of interviews you might meet some smart 19 year olds who aren’t even sure what they want to work on. Their chances of succeeding seem small. But again, it’s not their chances of succeeding that matter but their chances of succeeding really big. The probability that any group will succeed really big is microscopically small, but the probability that those 19 year olds will might be higher than that of the other, safer group.”

We can use this same approach to taking risks in our own lives. Put most of your resources into something safe while putting a small amount into extremely risky bets with massive potential.

An example of this for your career: keep your day job while working on a crazy startup at night.

If you’re operating in a random world you don’t want to have all your eggs in one basket. You want to be able to take a lot of small losses while being exposed to potentially massive wins.

3. Give Yourself Options

“[B]iology rarely rests with a single solution. Instead, it tends to ceaselessly reinvent solutions.” -David Eagleman, Incognito

An option is something you can take advantage of but don’t have to. If you buy a movie ticket then you’re guaranteed to be able to see a movie, but you don’t have to. That option cost you about $10. If a friend invites you to dinner it’s not a terrible cost to forgo the movie. A ticket to an AC/DC concert will be a much more expensive option.

Being exposed to more options means more potential opportunities.

Being able to move freely in life depends on the options you open up for yourself. Robert Greene explains how optionality is used in warfare:

“The world is full of people looking for a secret formula for success and power. They do not want to think on their own; they just want a recipe to follow. They are attracted to the idea of strategy for that very reason. In their minds strategy is a series of steps to be followed toward a goal. They want these steps spelled out for them by an expert or a guru. Believing in the power of imitating, they want to know exactly what some great person has done before. Their maneuvers in life are as mechanical as their thinking.

To separate yourself from such a crowd, you need to get rid of a common misconception: the essence of strategy is not to carry out a brilliant plan that proceeds in steps; it is to put yourself in situations where you have more options than the enemy does. Instead of grasping at Option A as the single right answer, true strategy is positioning yourself to be able to do A, B, or X depending on the circumstances. That is strategic depth of thinking, as opposed to formulaic thinking.”

The best generals aren’t the ones with the best plans, they are the ones who open themselves up to the most options.

In order to take advantage of these options one must be able to adapt.

Here are 5 ways to increase your options right now:

- Learn a new professional skill. If your company goes bust right now, would you be able to get another job doing exactly what you’re doing in your current gig? If not, you need to expand your skillset. This kind of learning can create asymmetric payoffs – skills often work together synergistically.

- Start a side hustle. Work on something on the side. Again, if everything goes to sh*t it’s nice to have options.

- Save money. It’s also nice to have options if things go well. Money in the bank gives you the option to take advantage of opportunities – be they investments or some amazing offer that requires you to quit your job. Money in the bank also makes it easier to transition if everything goes to sh*t.

- Go to parties. Opportunities often come in the form of humans – both personal and professional. One of the best ways to meet people is by going to parties. I hate parties until I get to them, then they are always worthwhile.

- Shift your perspective. I know. This is BS. But it’s also not. When you shift your perspective and become aware of more options, then you can take advantage of them. Train yourself to see your opportunities and what you could do to expand them even further.

4. Adaptability: Learn How to Perform in the Present

“The problem is that we imagine that knowledge is what was lacking: if only we had known more, if only we had thought it through more thoroughly. That is precisely the wrong approach. What makes us go astray in the first place is that we are unattuned to the present moment, insensitive to the circumstances. We are listening to our own thoughts, reacting to things that happened in the past, applying theories and ideas that we digested long ago but that have nothing to do with our predicament in the present. More books, theories, and thinking only make the problem worse.

Understand: the greatest generals, the most creative strategists, stand out not because they have more knowledge but because they are able, when necessary, to drop their preconceived notions and focus intensely on the present moment.” -Robert Greene, The 33 Strategies of War

Abraham Lincoln put it more succinctly: “My policy is to have no policy.”

Remember the WWI generals. They had access to decades of theory and planning when they entered the war. The first person to make a move that wasn’t in the playbook made all that theory irrelevant. Worse than irrelevant, clinging to old plans actually makes them harmful.

The war didn’t call for the generals with the deepest knowledge, it called for generals who were able to adapt to a rapidly changing situation.

We are in a similarly volatile situation today. Industries are completely changing shape in the time it takes college students to graduate.

If you want to be a writer you’re not going to take the same path writers in the past have. There are different demands on writers now. Publishing doesn’t work the same. Instead of waiting to get picked up by a publisher, you may need to release your own work on Amazon.

If you want to make movies, you may be better off starting a YouTube channel than working your way up the studio system. You’ve got to adapt to the new mechanics of the industry.

Even those who are looking to get a job need to adapt. Looking to the past might teach you that getting a degree (and then another) is the best way to get hired. Actually, you may be be better off creating a badass side project and showing it off online.

This world is changing so fast that no book (or even blog post) can give you a definite path to follow. You’ve got to quickly look around and act as best as you can given the environment you see.

Doing what makes sense in your specific circumstances will serve you much better than doing what you learned you ought to do in a situation similar to yours. There are best practices, of course, but until you grow past them it is impossible to fully take advantage of the randomness around you.

Robert Greene’s 48th law in The 48 Laws of Power is about remaining fluid. It’s about evolving into something other than you are in order to take advantage of a new situation. He explains the importance of adaptability in evolutionary terms:

“In the evolution of species, protective armor has almost always spelled disaster. Although there are a few exceptions, the shell most often becomes a dead end for the animal encased in it; it slows the creature down, making it hard for it to forage for food and making it a target for fast-moving predators. Animals that take to the sea or sky, and that move swiftly and unpredictably, are infinitely more powerful and secure.”

Just because you’ve mastered a skillset doesn’t mean that skillset will continue to matter. A friend of mine was a well-known wedding photographer. When digital cameras began taking over, he refused to adopt the technology.

After years of refusal he became a sort of novelty. For a window of time he was the person to go to if you wanted old-school film prints. Ten years later, nobody cared about film anymore, they just wanted great images. Now he has finally made the switch and is slowly building up his clientele again.

When a machine takes over your job your best bet is to learn how to use the machine. Don’t hold on to your old-school way in the name of tradition.

It’s easy to think of castles or fortresses as symbols of protection. We think that if we become strong enough nothing can harm us. Remember France’s Maginot Line? It was an impenetrable series of fortresses built as a reaction to the German invasion in WWI.

When WWII came around, the Germans marched right around the line, making it totally useless. The French, instead of looking around at their current circumstances, reacted to a previous attack. They prepared for the past instead of the future. They spent a massive part of their national budget on digging their heels in.

Their refusal to adapt was even more expensive.

5. Embrace the Undefined

“It’s also important to remember that no one is ‘the bad guy’ or ‘the best friend’ or ‘the whore with a heart of gold’ in real life; in real life we each of us regard ourselves as the main character, the protagonist, the big cheese; the camera is on us, baby. If you can bring this attitude into your fiction, you may not find it easier to create brilliant characters, but it will be harder for you to create the sort of one-dimensional dopes that populate so much pop fiction.” -Stephen King, On Writing

Our efforts to contain the world in a system or idea may be doing more to hurt us than help us. Instead of trying to find the answer, maybe we ought to embrace that there isn’t any answer besides what we do and what is.

Remember that this is true of both our external and internal worlds. John Kay describes the achievement of decision making under complexity:

“We do not solve problems in the way the concept of decision science implies, because we can’t. The achievement of the great statesman is not to reach the best decision fastest but to mediate effectively among competing views and values. The test of financial acumen, as described by Buffett and Soros, is to navigate successfully through irresolvable uncertainties.”

And so it is with our interior lives. At times it feels that we don’t know who we are. This would be bearable if we didn’t believe so intensely that we should know who we are. That we should be able to wrap up our identity into a box or sentence and serve it up to anyone who’s interested.

It’s not that easy, but it is that simple. Steven Pressfield has a suggestion for overcoming this dilemma in The War of Art:

“Are you a born writer? Were you put on earth to be a painter, a scientist, an apostle of peace? In the end the question can only be answered by action.

Do it or don’t do it.”

Let the actions you take define you and let the words fall away (they lie anyway).

Let yourself embrace the paradoxes of the world and begin to effectively mediate between the poles.

Let go of the need to explain and you’ll be amazed at what you do.

The aim here is to not just deal with the uncertain world that we have to live in but to embrace it — to love it. Nietzsche said it best:

“My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it—all idealism is mendaciousness in the face of what is necessary—but love it.”

Conclusions & Action Steps

“…it is much better to do things you cannot explain than explain things you cannot do.” –Nassim Nicholas Taleb

The world isn’t going to get any more certain. In fact, it looks like it’s going to get increasingly complex.

This doesn’t mean that we need to feel uncertain. It does mean we need to learn to operate under uncertainty more effectively.

I offered 5 specific ways in which you can go about doing this:

- Adopt Stoicism. Specifically practice the Triad of Control. Every time you feel disturbed by a situation, ask yourself what is in your control. Attach your mental well-being to your effort and the actions you take rather than the outcome. (Again, this is simple, effective, and incredibly difficult.)

- Make Small Bets. Think hard about small risks you can take that have the potential to pay off in big ways. Don’t focus on the possibility that you win but instead on the magnitude of the payoff if you do.

- Optionality. Give yourself more options in your life. Save money. Go to parties. Make your work public. Don’t commit until you need to. Get multiple offers. Always put yourself in situations where positive options are likely to be created.

- Adapt: Stay Present, Fluid. Stop reading about how to start a business and take the first step. Stop reading about fitness and go to the gym. Don’t think about what the book says you should do, think about what makes sense for you right now. The situation you are in is unique to you; a book or advisor may help you think through something, but only you fully understand the context of your situation.

- Embrace Uncertainty. Uncertainty is a force of nature; you don’t get to “beat” it, you can only hope to use it. How can you use it? Steps 1-4. How can you make room to begin applying those? Let go of your need for certainty. Begin to see that more ideas can be correct in the abstract — yet when you take action you find that only one reality exists. You can’t explain it all and you don’t need to. In fact, if you did, something else would just change. The goal is to love this. Amor fati!

Godspeed!